Out Damned Spot

Reasons and excuses, position and fault, responsibility and blame, inheritance and elections. Seeking cheap absolutions and blameless ignorance from the heart of the empire.

This essay is being cross-posted here on Substack. Visit The Reframe to see it on the main site.

The Reframe is totally free for all readers, and is made possible by its readers through voluntary subscriptions.

If you find value in these essays, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. It really helps writers to have patrons.

The trolley had arrived and the people had their levers. Some of them were tied to the tracks. The levers, if pulled in sufficient majority, would change the course of the trolley to kill fewer people. If not pulled, it would kill more. It would kill many either way.

The first person stood by the lever and pulled it. I am not to blame for the people the trolley runs over, they said, because more people would have died if I had not.

The second person stood by the lever and did not pull it. I am not to blame for the people the trolley runs over, they said, because I did not pull the lever.

The third person demolished the lever and the control panel. I am not to blame for the people the trolley runs over, they said, because the lever itself was corrupt.

As the trolley pulled forward, all three, who were riding onboard, loudly argued among themselves about which of them was most to blame for the death, within earshot of those tied to the tracks.

There's a moment in Steven Soderbergh's 2000 film Traffic where the newly freed drug boss says to the drug lawyer who had been working behind his back, "do you know the difference between a reason and an excuse? Because I don't." This is the point in the movie where the lawyer knows he is in deep shit, because that is a way of saying "I'm not buying your bullshit," and if newly-freed-drug-lords-behind-whose-backs-you've-been-working aren't buying your bullshit, then usually it is murder goon o'clock. (Who still talks about Steven Soderbergh's 2000 film Traffic? Me, that's who.)

I'm not a newly freed drug lord, so I do know the difference between a reason and an excuse. (This is my one advantage over my natural foe, the newly freed drug lord.) A reason is a causal explanation for an effect, and an excuse is a self-serving subset of distractions disguised as reasons, designed to place responsibility for the effect anywhere but on oneself, and designed to establish that whatever or whoever the cause of the effect and the responsibility thereof may lie, it doesn't have anything to do with me.

There's responsibility and then there is blame. If someone pukes in Mrs. Hondalink's 4th grade bathroom it might be the custodian's responsibility to clean it up, but the custodian isn't to blame, unless the custodian is the one who puked. (Even if the custodian puked, it may not be her fault. Maybe the lunch lady poisoned her.) But if the custodian, in full awareness of the puke, lets it set there for weeks, then the problem stops being puke and starts being a responsibility shirked, and the blame for that is clearly on the custodian, who inherited the responsibility. It really all comes down to whether or not the custodian decides to deal with the mess before her.

Responsibility is about position—proximity to the effect.

Blame is about fault—cause of the effect, or complicity in the cause.

Inheritance is about the matter before you, and the choices you are given, or not given.

If you benefit from something that's broken, you bear a portion of the responsibility to fix it. If you shirk the responsibility, you bear a portion of the blame. Therefore there often rises, in a fundamentally supremacist land like mine, founded in genocide and slavery, a desire to not know about brokenness or harm—to be ignorant of it. And if ignorance isn't an option, there is a desire to not be associated with brokenness or harm—to expunge the association.

Excuses serve to negotiate away blame and responsibility.

So I'm thinking about reasons and excuses, and responsibility and blame, and position and fault; and the reasons I've had for things I've done, and the reasons I have, and the excuses I've made along the way; and all the other excuses I've been tempted to make, and the sources of those temptations.

And, because the election is upon us, I'm thinking about the ways most of us are talking to each other about the election, and the ways we use it for reasons and excuses, and the reasons and excuses we have for doing that.

And, because it is such a current and pressing (as opposed to it being the only) example of the uses of American empire and military, I'm thinking about the genocide that Israel's far-right government is conducting in Gaza and beyond—the mass killing through neglect and deprivation, and the mass killing done with bombs and other weaponry—and the way my country has given the necessary political support to the Israeli government that is enacting it and to the authoritarian who leads them, and the way my country is providing the bombs and other weaponry, and the way my tax dollars directly fund the killing, and all the responsibility and blame that comes along with that, and all the excuses that I give and the excuses I hear given, especially over the course of the election, to shift responsibility and blame about this.

Supremacy is a real excuse engine, I've noticed. It's a real blame delivery system.

And it's an inheritance.

This is a very long one, I'm afraid. I tried to split it and I failed.

To help you out, it's categorized so you can take bathroom breaks and whatnot: Inheritance, Reasons, and Excuses.

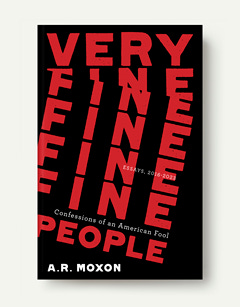

My book of essays, Very Fine People, is now available. Click to buy personalized signed copies or direct purchase at a discount.

Inheritance

As for supremacy: I wrote a book that came out this year about things I learned when Trump became president, which were things a lot of people less lucky than me had already known their whole lives, which makes me a fool, and is why I subtitled the book Confessions of an American Fool.

Supremacy is the idea that some people's lives matter, and everyone else's lives do not. It's the idea that those whose lives matter get to do whatever they want to the people whose lives don't matter, and despite the abuse still think of themselves as not only good but blameless, perfected already, exceptional. Supremacy is the founding myth of my country, the United States: which settled an already settled land and murdered those who lived here by the thousands and millions and worked to demolish their cultures; which enslaved others by the thousands and millions, and forced them and their children after them, and their children after them, and so on, to live lives of brutal enslavement; which told itself many self-absolving stories of its own bravery and heroism and goodness for having done so; which still tells itself those same stories.

Supremacy is a vile lie. It denies the truth that every human being is a unique and irreplaceable work of art, and insists that life must be earned, insists that those who have not earned life represent, simply by existing, a theft and a crime against people who have earned life, and deserve hard use or death at the hands of those who have earned life, because violence in the hands of people who matter is a redeeming act that delivers safety and peace, and any violence that comes in return must be taken for an unprovoked aggression demanding increased and accelerating violence as defense. So it is that supremacy always explains that there are a whole lot of people who unfortunately speaking but pragmatically speaking are going to have to die, because that's just the way things are.

It's a very popular lie, supremacy. It's the foundational and dominant spirit of our country. And this is, I think, because it is inherited. Many of us, millions and tens of millions, were raised with the unquestionable idea that we were exceptionally good. We inherited a blamelessness that is impervious to any fault. We inherited a self-bestowed heroism that is impervious to any villainy. We inherited a self-bestowed absolution without having to admit to crime. We inherited the right to not know what we had done to others, and call ourselves wise and just for our ignorance.

Yet many others of us in the United States, millions and tens of millions of us, inherited something very different: We inherited the knowledge that to people who matter, our lives represent a theft and a danger simply by existing; that we have, simply by existing, deserved hard use and death at the hands of the blameless people who have earned life; that we, because we are deemed theft and danger, are to blame for the theft and the violence committed against us. (And I say us and we in this paragraph, even though I am part of the first group, not to claim any of this moral clarity and authority, but to recognize that all are all our friends and neighbors, are our fellow lovely unique and irreplaceable works of art.) For those of us who have inherited not plenty but lack, not blamelessness but fault, there was never any luxury of ignorance about American supremacy. There was always a knowledge of what it was and what it did, because those of us in this group are the ones to whom it has been and is being done. And this knowledge made those of us who inherited lack and harm and blame inheritors of awareness rather than ignorance, and access to moral clarity and moral authority of truth rather than comforting and self-absolving lies.

A lot of us in the first group—mostly white, mostly male, mostly able-bodied, mostly cis, mostly straight, mostly Christian, and property-owning and employed and housed—still live in the deliberate ignorance and blamelessness of American supremacy, and are willing to die for it and kill for it, even though it is killing us.

However, a lot of us in the first group of privileged inheritors reached a point of shock that broke through our inherited ignorance. For me, as for many, it was a slow trickle of things, starting with the "War On Terror" and everything that came with it, continuing to the ongoing revelation of racialized and institutionalized police brutality and murder over the last decades—but the breaking point was the rise and election of Donald Trump. For others it came earlier. For others I know awareness is still to come. For some it will never come.

Those of us who have entered awareness can see these willing supremacists very clearly, and can detect their reasons—which is that they want supremacy for its unnatural and cruel rewards of blamelessness and absolution and the exclusive right to punishment—better than they can. Those of us in awareness can see their excuses for what they are, too; that is, as the desperate attempts to hold onto their unearned inherited blamelessness and absolution, even as they pursue violence and malice and cruelty and death.

So we inheritors of supremacy—inheritors of heroism and blamelessness and absolution and exclusive right to punishment—awoke, and now live in a deepening awareness rather than stultifying ignorance ... and I say good for us as far as that goes; good for us, as long as we don't malinger in awareness and never progress from it; good for us, as long as we use awareness to change into something better, become people who repair what is broken and pay the cost for doing so.

However: I can speak to the temptations that arise when one becomes aware of belonging to a country founded in genocide and slavery, still dominated by a supremacist human spirit. I can speak to what happens when one privileged by such a system becomes aware of the ways one still benefits directly from those things.

What happens is that I (and you too, if you're like me) begin to sense that this awareness of the vile lie of supremacy threatens to take us on a path far away from our supremacist inheritances of heroism and absolution and blamelessness, far away from our exclusive right to punishment. And we feel the lack of our benefits, and begin to want to get those things back, as quickly as possible.

We also don't want to give up what we can see we stand to gain from awareness. We want to claim what we see as our share of the inheritance of moral clarity and authority we sense our newborn awareness confers. But we also want to be the heroes of the story again, or if we can't be the heroes, we at least want to be absolved, and if we can't be absolved, then we want to solve the problem with punishment.

And we say Not All Men. And we say Not All White People. And we say Not All Christians. And we say Not All Americans. And we say many other things as well.

And I ask you, my fellow people of privilege:

Do you know the difference between a reason and an excuse?

And I ask myself:

Do I?

I'm not so sure about myself. Maybe you're more confident than me.

But I said I would talk about the election, and the genocide in Gaza.

And I'm about to tell you how I voted, and why.

This essay is cross-posted on Substack from The Reframe, a free publication supported by its readers through a pay-what-you-want subscription structure. (Click for discount codes.)

Want to make sure you never miss an essay? Subscribe on the main site.

Reasons

In doing this I'm not telling you who to vote for, though I imagine sharing my perspective does confer some necessary sense of prescription. I offer this caveat because I've notice that very frequently when somebody tells you who they voted for and why, people who made different choices feel compelled to tell you what they did, and why, and what that means about them, and what that means about you. This happens in a way that conveys the idea I feel that your expression of your choice is a direct accusation of me, one that demands a defense.

There seems to be something of accusation and defense around these conversations, is what I've noticed.

Sometimes some of this is implied, though often it is not. But I can't help but notice that when this is done, it is very often done with the clear message: because I have done differently than you, you are now to blame, and I am not. You are responsible, and I am not.

And sometimes people have reasons for doing this, so I tend not to participate in election arguments these days. My examination of my inheritance of American supremacy, and my attempts to align against it, have made me very skeptical of attempts to shift blame off of oneself and onto another. So I will tell you what I did this election, presented as a decision for which I credit and blame only myself.

I voted for Kamala Harris.

I did this even though terrible things are currently happening—some of them despite and some of them with the cooperation or active participation of the party she now leads—many of which will very likely continue to happen if she wins. To give the most pertinent (though not the only) example of what I mean by "terrible things," I return to the fact that some of the most upsetting things many of us have ever seen are being enacted by the far-right authoritarian government of Benjamin Netanyahu and the Israeli government against Palestinian people in Gaza¹. This has been the situation for decades, but the acceleration has been stark in the last year.

I won't list all the atrocities here, because if you don't know there are many good journalists and writers you can turn to, but also because if you don't know by now I feel like you don't want to know. I have seen people burned alive in hospitals. I've seen reports of children systematically shot in the head by snipers. I have seen residential high-rises bombed into rubble. I've seen death from deliberately manufactured starvation and thirst, and I have heard the most chilling language of dehumanization and the most direct calls possible for extermination. All of this sort of horrific thing in Gaza and elsewhere has received "ironclad" bipartisan political support from my country, the United States, over the course of my entire life, stretching from this very moment to the decades far before I ever entered awareness about the spirit of American supremacy that fuels the imperialism and capitalism that grows out of it.

Kamala Harris has called for a ceasefire, but she hasn't called for the weapons and bombs to stop coming from her administration. And in the Democratic platform support for Netanyahu's government remains "ironclad." This should perhaps not come as a surprise. What I've learned is that the atrocities that arise from supremacy are often bipartisan. There are always people tied to the trolley tracks. This is the sort of realization that can make awareness a very high price to pay; a horror, really. It can be tempting, especially if you were born into it, to want to return to supremacist inheritances of ignorance and blamelessness and absolution.

So does my vote for Kamala Harris make me complicit in these atrocities?

Many will say yes. And some will have good reasons for saying so, which I'd like to get to in short order. But first, just for a moment, I'd like to back up from the election and voting to take a broader look.

Whatever I do in election season, I am complicit in terrible things—both things the accelerationist Nazi/Republican supremacists do, and things the status quo/accommodationist Democratic supremacists do. We should be clear about my complicity in American supremacy as a present reality. My tax dollars help fund the military industrial complex that make the bombs, that pay the police, that fund the harm done at the border, and more. I don't stop paying taxes, because I'm not willing to go to prison. I don't stop working, because I need to live and provide for my own family. I could make excuses, but these are the reasons. I'm not willing to go to prison for not paying taxes for the money I earn. I'm not willing to stop earning money to care for myself and my family. Perhaps I should be willing. Perhaps you should be, too. I don't, though, and maybe you don't either. My complicity remains, and so does that of Kamala Harris, and also of the Democratic party as an organization, even if I wish it weren't so.

I am complicit in the atrocities in Gaza, and many other crimes against humanity as well. I hope to be aligned against them, and I realize that acknowledging one's own blame is something that supremacy can never ever do, so I recognize that the first step of aligning against supremacy is acknowledging my blame.

So: I am complicit. Let's close the door on that one.

Does my vote make me complicit? Some would say yes. I think some have their reasons for saying so. If my family had been murdered with U.S. bombs or was under the threat of it, and both parties supported the government doing it, I don't really think I would be able to tell much difference between the parties, even if the differences existed. I think I would feel like the world had ended already if my family had been murdered; I don't think I'd be capable of heeding the warnings any longer that the world was in danger of ending. And I think there are people who have seen the horrors coming out of Gaza who are so traumatized by the gravity of it they might just not be able to engage anymore with the political process. There may be people who have fallen into despair that this process will ever move to protect them or others. I think those are reasons, not excuses, and I think the Democratic leaders who made these their policy choices are going to have to live with the effects of those reasons, whatever those effects turn out to be. And so are all the rest of us.

But I did vote for Kamala Harris, for reasons I hope to get into in short order, and which I hope will be free of excuses.

And also to answer the question: Does my vote make me complicit?

I voted for Kamala Harris, as I said. And I voted for all the other Democrats on the ballot. I did it even though I know terrible things are currently happening under our Democratic presidential administration—some with its support and endorsement, some not—and are likely to continue.

My reasons are many but can be boiled down to two. First, if Donald Trump wins, all those terrible things will continue and worsen, and many many other even more terrible things are very likely to begin. The second reason is that if Kamala Harris wins, many things that represent progress and improvement and healing and repair are more likely to happen that would otherwise not. I do not want the terrible things that are already happening to worsen, nor do I want all the many terrible things to begin, and I do want to see improvements occur. So I have voted for Kamala Harris.

Donald Trump is a Nazi—an open Nazi—and Kamala Harris is not. He will use the military to go after his political opponents and against leftist protesters. He will round up millions and millions of people and put them in camps. He will appoint more and younger bribed corrupt judges on behalf of creepy Christian religious bigots who want to control our lives and bodies, as part of a mission to cement the United States as a dictatorial far-right theocratic ethnostate. He will not only support our gangs of brutes we call police, but encourage them to greater and greater violence, in coordination with militarized white supremacist militias. He will oversee a national abortion ban. He will effectively demolish what is left of democracy in this country. He will subject trans people and gay people and Black and brown people and immigrants and non-Christians and labor leaders and those deemed "Marxist" to malicious campaigns of terror and brutal and murderous pogroms. This is not speculation, they are his campaign promises, and he is well-supported in his intentions by courts and cronies, by money and power, and by tens of millions of voters. He frequently fantasizes about using nuclear weapons, which would reduce our planet to an irradiated cinder. He wants to accelerate every single driver of our incipient climate catastrophe.

These are very very good reasons to vote against him, I think. People often issue the challenge: name a reason to vote for Kamala Harris without saying that she isn't Donald Trump. This to me ignores the fact that not being Donald Trump is an extremely good reason to vote for somebody, when Donald Trump is the alternative. I fear for my children. I fear for my friends and neighbors. I fear for trans people and other people in the queer community. I fear for immigrants both documented and undocumented, and all of the people who Christian Nazis believe look like immigrants, including Americans who are Palestinian—a term Trump uses as a slur. I fear for everyone who will feel the effects of climate change in a world directed by a dictatorially authoritarian American ethnostate headed by the apocalypse cult that calls itself "Christian," which means I fear for everyone, and so at last I must admit that I fear for myself.

There are also positive reasons to vote for Democrats. I vote for Democrats despite their failings and complicities because on a national, state, and local level, they have passed voting rights bills, and child welfare bills, and education bills, and climate bills, and abortions rights bills, and have funded social infrastructure, while Republicans have blocked all these efforts and sabotaged them as much as they can, wherever they can, and lied about doing so, and then blamed the Democrats they sabotaged for the effects of the sabotage. Even on the matter of Gaza, I vote for Democrats because they have in their caucus members who do want an arms embargo and an end of our support of the Netanyahu government and all the death and instability it brings, and Republicans do not, and because Netanyahu openly wants Trump to win, and I believe he has his reasons for wanting that. I vote for Democrats because where Democrats are in power, more people who would become more abused and more harmed become more free and more safe, even though I recognize the disturbing reality that all people do not.

So those are my reasons.

Excuses

I know how we talk to one another around election time. I don't think there are any non-fascist reasons to vote for Republicans, and I've grown exhausted of cataloguing the various excuses for doing so over the years. I've listed non-fascist reasons to vote for Kamala Harris and Democrats, and to vote against Trump and Republicans. I've earlier mentioned that I think there are real reasons that Democrats and Harris have given people to not be able to bring themselves to vote for them and her, no matter how distressing I may find that truth.

I think those are the reasons.

I'd like to talk about excuses now.

I'd like to return to an earlier point, about the fact that so many of us, raised in the inheritance of supremacy's unnatural advantages of absolution and heroism and exclusive right to punishment, still want, even in our new awareness, to keep those advantages. To make sure that we are still the heroes, or, if not the heroes, at least not to blame. Or, if still to blame, at least not most to blame.

I think a lot of people have a belief, perhaps examined, perhaps not, that their participation or their non-participation in American electoral politics somehow delivers them exoneration from their inheritance of complicity in the effects of American politics.

A lot of people who are least threatened by American supremacy talk about their vote for Kamala Harris—for which they may have good reasons—as though it grants them absolution for anything that might come after the election.

A lot of people who are least threatened by American supremacy talk about their inability to vote for Kamala Harris—for which they may have good reasons—in the same way.

If you don't vote, you can't complain, is the phrase. With it comes the corollary: I voted, so I can complain, and I will complain about you. Therefore I am not at fault, and you are. Therefore the responsibility is no longer mine, it is yours.

It's sad that genocide isn't a red line for you, is another phrase. With it comes the corollary: genocide is a red line for me. Therefore I am not complicit, and you are. Therefore I am not at fault, and you are. Therefore the responsibility is no longer mine, it is yours.

I don't think that's what voting does, especially not for those of us who are advantaged by our supremacist system. Voting strikes me as a lever of power. A simple one, and a tiny one, and an imperfect one. There are bigger levers of power than the vote, but they are harder to do and more personally costly. I suppose there are some among us who do all the harder things but don't do the simplest thing. I do wonder if there are a lot of people like this, though.

The idea that it's a lever makes me brings me back to the trolly problem, that old saw about complicity and choice that doesn't leave us any easy outs. To pull the lever or not doesn't take you out of the trolley problem. The point of the trolley problem, I think, is there is no out. There is only a choice and living with it. Or deciding not to live with it, by retreating to old supremacist inheritances, with excuses that shift blame and responsibility off of oneself and onto others.

The thing about our trolley problem is that our people with levers—us—don't stand to the side. Some people with levers ride the trolley, and some are tied to the tracks, and may even be about to lose their levers, or even their lives.

Some people are more to blame, and others aren't. But I think whether or not they are to blame is less a function of their levers, and more a function of whether or not they are one of those who have a trolley ticket, or are one of those tied to the tracks. Those tied to the tracks all make a full range of available choices in elections, so the difference isn't always evident. And for those of us riding the trolley, whether or not we agree with their position pales beside the fact that they are tied to the tracks and we are not.

I become very suspicious of my own urge to take myself out of the trolley problem. I have become very suspicious of the easy temptations to scold people in order to establish my own blamelessness, or to expunge or minimize my complicity, when I know there is a ticket in my pocket.

To scold somebody whose family is tied to the tracks for how they pull the lever seems to traffic in supremacy, when you have a trolley ticket. So does scolding somebody whose family has already been run over for not pulling it. So does celebrating yourself for pulling the lever that sends the trolley toward fewer people, even as the people die beneath you. So does celebrating yourself for not pulling it, because no matter what happens, at least the levers lack your fingerprints.

I know that there are people who will tell me that a Donald Trump presidency cannot result in more atrocities, because there are already atrocities happening. And I suppose that it is possible to ignore the fact that worse is possible, on the basis of the fact that bad is already here. It is possible to ignore the clearly worse intentions of those who would seize power, and the strong likelihood that they will be successful at what they intend.

I know there are people who claim that there is absolutely no difference between the parties, to focus only on the many points of similarity, and to ignore the many tangible differences in policy and results and rhetoric that do exist, and will matter to millions and millions of people who will face far worse given one outcome over another.

And I know there are people who insist that Democrats aren't complicit in any of this at all, or insist that the good that they do cancels the bad, which I suppose relieves some of the internal tension in their minds.

We can do this. We really can. It's possible to enter ignorance again. I can't help but notice that this is what fascists want us to do. I can't help but notice that false equivalencies that flatten and ignore their intentions benefit people with the worst intentions. Entering these ignorances again doesn't make us fascist, I suppose. But it doesn't differentiate us from them, or set us in opposition to their intentions.

I know people return to the old supremacist inheritances of punishment, too.

I know there are those who have or will vote for Kamala Harris who will respond angrily to people who can't bring themselves to do the same, and tell them that they are the ones to blame for what will come when the far worse option gains power. I know there are some who will even tell these people that they deserve what they will get.

I've seen privileged people of awareness cheer themselves that if Trump and his Republican Nazis win, then at least the people in the red states, who did not vote as we did, will feel the most harm first—ignoring that the harm in these places will come first to those who were already most threatened, the same people whose lives we have claimed matter, from our yard signs and bumper stickers.

We can I suppose blame people in despair—who are most harmed by power, who have the least access power and political representation—for the harm and abuse that is coming first and most brutally to them. We can. It doesn't make us fascist to do so, I suppose. But it doesn't differentiate us from them, or set us in opposition to their intentions.

I've seen privileged people of awareness proclaim that it would be better if Trump and his Nazis rise to power, because Democrats must be punished for their complicity, or proclaim that there is no solution but for the entire system to collapse—ignoring that the punishment and harm in these scenarios will not be experienced by the Democratic establishment, but by all those who are most threatened, all those with whom we claim to stand in solidarity.

We can do this. We can hope for this punishment to come. We can hope for collapse of the system and all that comes after. We can. I can't help but notice that this is what fascists most want, too. Wanting it doesn't make us fascist, perhaps, but it doesn't differentiate us or set us in opposition to their goals.

And I can't help but notice that the impulse here in all cases seems to be to shift blame. I can't help but notice that the impulse here is to tell people that they have deserved violence and death. I can't help but notice how this aligns with the supremacist urges toward blamelessness and cheap self-absolution.

It doesn't make us supremacist, perhaps. If it doesn't, it doesn't differentiate us, or set us in opposition to supremacy's goals.

Here comes the question again, so I suppose I must answer.

Does my vote for Kamala Harris make me complicit in the dominant American spirit of supremacy?

My answer is yes. It must be a component of my complicity, just as not doing so would be a component of it if I did not. To what degree? I honestly don't know. I know I already am complicit, but I'm not trying to shed my complicity as a first priority, and shedding my complicity is not what I was trying to do with my vote. If I can protect some, I will, even as I must admit that among those I am protecting are myself and my family. If that makes me more complicit in what is to come, I will pay the added price of responsibility and blame. Perhaps if I was willing to pay much steeper prices I would finally shed my complicity, but I suspect people who pay steeper prices—in earlier days we might have called them saints—have gone far beyond the desire to be personally absolved.

A question for fellow Harris voters: Do you think your vote sheds you of complicity for whatever Trump will do if he wins? Is that what voting is for you?

A question for non-voters: Do you think not voting sheds you of complicity? Is that what voting is for you?

However you vote or don't, is not being personally complicit your priority?

Or is what you most seek the old supremacist inheritance of punishment?

Who among us wants to keep the inheritance of moral understanding that comes with awareness, but wants it without paying the price? Who among us also wants to restore their inheritance of absolution and ignorance and punishment?

We who are privileged by American supremacy all have blood on our hands, and it's not ours. Is our first priority thrusting our hands into the wounds we see before us, to stop what bleeding we can? Or is our first priority to wash the blood from our hands, no matter the cost?

Do we know the difference between a reason and an excuse?

Some parables are more challenging to live up to than the teller is capable of. Here is one.

As the trolley pulled forward, all three, who were riding onboard, loudly argued among themselves about which of them was most to blame for the death, within earshot of those tied to the tracks.

A fourth person, standing by their lever, heard them arguing. The fourth person pulled their lever and then climbed down from the trolley, lay down on the tracks directly before its wheels, and waited. I'm sorry, they called out to the others tied there with them. I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I'm sorry.

The Reframe is totally free, and is supported voluntarily by readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor at The Reframe. Pay whatever you want.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the essay collection Very Fine People, which you can learn about how to support right here. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. In and out of the garden he goes.