Peaceful Solutions

On respectable and profitable human-suffering engines, the murder of a CEO, propriety in a land where life has been cheapened, and some good news for those who seek peaceful solutions.

This essay is being cross-posted on Substack, which is no longer hosting my subscriptions. Visit The Reframe to see it on the main site.

UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was murdered on the streets of New York last week, gunned down on his way to an investors' meeting. There's a manhunt for the killer, and the murder has dominated news coverage in ways that the thousands of other gun murders that occur every year across the nation have not.

There's also been quite a lot of talk online about whether or not he may have deserved it, or at least that he might have had it coming, and there have been a lot of jokes about denying sympathy due to pre-existing conditions, and tens of thousands of laughter emoji reactions on the UnitedHealthcare webpage, and so on and so forth, and this sort of thing has caused quite a bit of consternation, given that murder is generally understood to be a bad thing, and most of us generally don't want to live in a world where people are gunned down in the street. Many people detect in this response a disgustingly callous disregard for human life. So it is that from the halls of power and corridors of justice and on the platforms of influence, we are reminded that Brian Thompson was a human being, and that he had a family who loved him, and that violence is never the answer, and that we must always seek peaceful solutions—and who could argue against seeking peaceful solutions? I won't. Who would say that Thompson was not a human being or deny that his family loved him? I don't and won't. Who thinks violence is the best solution to problems? Not me.

Speaking of violence: lLast year a homeless man named Jordan Neely was choked to death on a subway, and last week his killer—an ex-Marine named Daniel Penny—had second-degree manslaughter charges dismissed against him, though he still faces a less-serious charge of criminally negligent homicide (he faces 4 or maybe 0 years in prison if convicted). And ever since this killing, there have come from the halls of power and the corridors of justice and the platforms of influence a steady stream of explanations why Jordan Neely may have deserved what he got, or why the killing might not be such a tragedy, and why violence, while regrettable, is sometimes the answer, and why peaceful solutions, while desirable, are sometimes just not possible. Did Neely have a family? Did they love him? I haven't heard. There doesn't seem to be much curiosity on the topic. All this has caused quite a bit of consternation, though not necessarily from the same people consterned by the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. But many, particularly those who feel that they have also been made vulnerable by the same systemic failure that failed Jordan Neely, detect in this response to Neely's murder a disgustingly callous disregard for human life.

Some might think I just changed the subject. Let me talk similarities.

Everyone involved in both stories is a human being, unless you ask our society—the parts of it where power is negotiated and narratives of permission are generated, anyway. In the corridors of power, the halls of justice, on platforms of influence, some people in our society are clearly deemed to be human beings—their lives justified, their potential valuable, their deaths tragedies—while others are deemed to be nothing more than a danger, a drain, a discomfort, a problem to be solved by making them not exist quite so much. The primary dividing line appears to be whether you've got money, or, failing that, whether you can make somebody money.

We're talking about Jordan Neely and Brian Thompson, but we could be talking about many things. We could be talking about the immigrants that Donald Trump and his fascist party are dehumanizing by framing them as an infectious disease, and vilifying them by casting them as a threat to national security, and terrorizing them by getting ready to deport them and their citizen children. We could talk about recent revelations that Trump thinks that disabled people should just die, or the ways that our society is primed to accommodate that viewpoint. We could talk about how world's richest man Elon Musk has been appointed to a draconian and corrupt and totally fabricated "efficiency" agency, and how he has proposed cutting all veterans' health benefits, which will grow the ranks of the unhoused and untreated. We could talk about how the presence of people from Black and other historically marginalized communities in spaces from which they had previously been excluded is being treated as a foreign invasion and an existential danger by federal judges and other powerful white supremacists. We could be talking about any number of things that clearly demonstrate the core traditional spiritual belief of the United States that life must be earned, and making money is how you earn it, that clearly demonstrate the dominant belief that if you haven't earned life, then you are a question to which violence is often the answer.

Jordan Neely wasn't making anybody money, that's for sure. He was understood to be a danger to himself and others, even though he was the one who was murdered on that subway, so pretty obviously it was he who was in the most danger, as unhoused people almost always are. Maybe Neely even was a danger; unhoused people tend to be desperate, after all, and desperation can make people unsafe. But I also remember that we live in a world where millions of people are systemically abandoned to suffer and die on the streets even though housing them would be cheaper, and I note that it is not the people suffering homelessness who decided to make society work that way, so we might wonder if it was Jordan Neely creating the danger, or if it was someone else making a choice somewhere else.

Speaking of making choices that create dangers for others, UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson was making people an awful lot of money. He grew profits for his organization by tens of billions of United States dollars, and for that service he was paid tens of millions of those dollars. We might look at how it was that he made himself so valuable a person during his life that his death should be an occasion for those in the halls of power and the corridors of justice and the platforms of influence—who are so frequently forgetful about the humanity of others—to remind us so frequently of his humanity.

What is it about this murder that makes so many people remember that violence is never the answer, particularly when those same people usually spend their time explaining why most instances of empowered violence, while regrettable, are inevitable, or even necessary?

What is it about this specific killing that made people who usually spend their time defending violent solutions start to become so enthusiastic about peaceful ones?

The Reframe is totally free for all readers, and is made possible by its readers through voluntary subscriptions.

If you find value in these essays, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. It really helps writers to have patrons.

Thompson made his millions and made his company its billions by running a very profitable machine that creates human suffering, called a health insurance company. This sort of human-suffering machine creates wealth by putting itself between healthcare and patients, and then by denying that healthcare, or at least denying to pay for most of it. This forces sick human beings to make the gut-wrenching decision of whether to be financially ruined or to "just die" (to quote our incoming president). It forces the loved ones of sick people to watch their spouse or parent or children die from neglect, and often to watch them suffer unimaginably on the way to dying. It's an industry that eats vulnerable people.

It's the sort of unimaginable cruelty that you would think would be treated every day as the shockingly callous disregard for human life that it is—if you are the sort of person who is actually shocked by callous disregard for human life, that is, and not simply interested in upholding a monstrously cruel status quo. The tens of millions of people who have been financially ruined and who have died suffering needlessly from engineered systemic neglect also were human beings, just as Brian Thompson was, and they also had families that loved them, just as Brian Thompson did. By the tens of millions, the survivors also mourn the killing of their loved ones—whose deaths, while enacted by deliberate choice and with clear motive, are not deemed murders, because the decisions that caused their anguish and death were legal, and, more to the point, were extremely profitable.

According to reports, UnitedHealthcare denied more health claims than any other provider, which made it more profitable, which made it more competitive, which means that it's more and more likely that more and more people will be denied medical care by other providers, and more and more people will be financially ruined, and more and more people will spend the last years and months of their lives crushed as much by unfeeling and needless bureaucracy as by sickness, leaving behind millions and millions of traumatized surviving loved ones.

So that's how Brian Thompson became such a valuable life in a country where so few lives are valued: He ran one of the most profitable human-suffering engines in the whole country. He made mountains of money for a few people, all of whom already had more money than they will ever need—a list that includes himself and his surviving family, who loved him.

This reminder about Thompson's family goes out regularly, because, again, a lot of people have declined to mourn the death of the man who ran the most competitively cruel human-suffering machine in a country full of them, and many even seem to be cheering it, and this makes people in the halls of power and the platforms of influence extremely nervous. They remember Thompson's humanity, even though "humanity" is something they seem largely forgetful about when it comes to all the millions of people—sick and desperate and often on the streets like Jordan Neely—who suffer and die every year because of the effects of extremely profitable and respectable human-suffering engines, which are run and maintained by human beings because somebody has to run them, because a human-suffering machine is deemed an intractable part of the way we do health care. Intractable, not because it actually saves money or returns superior results, but because it makes profits, and profits are the point of our health care system, and this is not controversial or shocking in the same way as ten thousand laughing reaction emojis on Facebook are. Brian Thompson's murder won't stop the human-suffering machine or probably even slow it down. Somebody else—probably someone also with a family who also loves them—will run it now.

It's interesting that people so committed to normalizing human cruelty would be so surprised to see it reflected back at them. As a society, it's already been determined that millions of human lives are a perfectly acceptable cost of doing business. Those who wanted it that way paid a lot of money and killed a lot of people to make it so. They should perhaps be less amazed when people whose lives they intended as payment meet them on the shockingly heartless field they insisted upon.

It seems to me that some of the wealthiest and most powerful individuals in our society think they can create one kind of world for everyone else—a world where human life is disposable and as cheap as it can possibly be made—but then think they don't have to live in the world they've forced us all to occupy. They think they can make a world where some people matter and other people don't, and in so doing will remain perpetually the ones who matter.

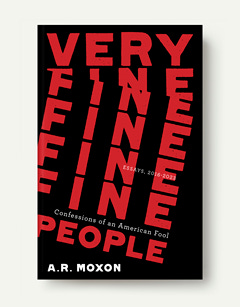

My book of essays, Very Fine People, is now available. Click to buy personalized signed copies or direct purchase at a discount.

They're certainly going to try to make it so. There are shocking policies already in place and even more shocking ones being proposed. I think we will find that wealthy and powerful and influential people, who have decided that our healthcare system is very complicated and its problems intractable and unsolvable, will suddenly find that structural changes have become very simple and easy when the topic is not the overall well-being of humans in society, but rather the safety and security and reputations of those who generate profit by destroying the overall well-being of humans in society. I think the murder of a CEO will be treated as dangerous, in a way that millions and millions of people suffering for years in despair and dying broke decade after decade never has been, because our society values corporate profit over human health.

Yes, they'll try to make us live in one world while living in a different one. And for a while, that might even seem true—but it's a lie.

The truth is, we all live in the same world.

It seems to me that when you create a world where human life has been made as cheap as possible, you will eventually find you live in a world where your human life is deemed by others to be cheap, too.

It seems to me that when you create a world that is deliberately callous about human life, you live in that world—which might be a problem, if you are a human.

This essay is cross-posted on Substack from The Reframe, a free publication supported by its readers through a pay-what-you-want subscription structure. (Click for discount codes.)

Want to make sure you never miss an essay? Subscribe on the main site.

Does all this sound like I'm advocating violence? I'm not. I'd like a peaceful society. I just happen to remember what exactly it is that fosters a peaceful society, and it's not respectable profitable machines that run on unimaginable cruelty and create widespread human suffering and tens of millions of desperate people.

Do I celebrate the murder of Brian Thompson? I do not. I'd like a world without murder. I also know how many people our healthcare system murders every year—murders, no matter what our halls of power and corridors of justice or platforms of influence say. And I know how close most of us are to falling victim to these respectably profitable human-suffering machines, because we all have human bodies that will get sick and old over time, and most of us do not have vast wealth cocooning us.

Was the death of Brian Thompson a crime? It was. The question that's not being asked in the halls of power and corridors of justice and on the platforms of influence is, what type of crime was his life? I think you write your obituary in life, not at the point of your death. Some people make their lives into something that causes millions to mourn, and as a result of that, the end of their lives cause people some relief from that mourning, and relief rather naturally makes people celebrate. That's not something the celebrants are doing to the departed; it's something the departed did to all of them. When most people die, it is compassionate behavior to reflect on the departed’s life and send sympathy and support to the deceased’s loved ones, because this is how we honor our shared humanity. When some people die, it is compassionate behavior to reflect on the departed’s life and send sympathy and support to the deceased’s victims, not because we do not honor our shared humanity, but because we do. We remember the lives lost, and why they were lost. And we mourn, and we do not disparage those who mourn if they are not seemly in their mourning.

Do I think the reaction to this murder is unseemly? I don't think seemliness is our issue. I think cruelty and greed is our issue, whereby our society categorically rejects the notion of seemliness.

Do I agree with the TV and newspaper pundits that violence is never the answer? I would hope to be one who is not oriented toward violence. I wonder at those who only ask the question of the less powerful, who never apply the question to all the violence we accept as a part of regular daily operation of our status quo. I notice that violence very often is framed as the answer, actually, and by the same people who are now asking—as the exclusive property of the wealthy upon everyone else. The consternation seems to be saved not for the violence, but the reversal.

Don't I agree that we should seek peaceful solutions? I do. And there is a peaceful solution to the depredations caused by our cruel and inhuman privatized system, and that is to destroy the cruel system. Universal healthcare coverage is the peaceful solution here, so if someone is looking for peaceful solutions, point this out and see if “peaceful solutions” is what they're really after, or if they just want sick people to die quietly while very nice human beings with loving families step over whatever dead body just hit the sidewalk on their way to the board meeting.

The peaceful solution to problems caused by our machines of human suffering is to completely dismantle our machines of human suffering, and to pay the cost of doing so. This isn't an ultimatum or a threat, it's simply stating the obvious, which is that engineering death and suffering and despair on a mass scale will never create conditions of peace, even if it will make a buck.

We'll find peaceful solutions once we align ourselves with a spirit of peace; once we determine that life is not something to be earned, once we reject our terrible foundational lies.

We need peaceful solutions to a great many problems, and I would certainly welcome anybody who wants to seek peace for all, rather than just the silence of victims on behalf of abusers.

We all live in the same world.

If we want to live in a peaceful and kind world, we must work to make one. The more power each of us has to shape the world, the greater the responsibility we bear for the world as it's shaped.

If those of us with the power to make a peaceful world refuse to make one for others who are struggling to survive, how can we ever expect to live in a peaceful world ourselves?

The Reframe is totally free, and is supported voluntarily by readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor at The Reframe. Pay whatever you want.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the essay collection Very Fine People. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. He has made himself practically extinct from doing things smart people don't do.

Violence is never a _good_ answer, but it is far too often either the answer we are given or the only answer we have. At this moment in our society it may be the only thing that causes change.

It takes most people fifty or sixty years to figure all of this out, to fully grasp the extent of the lies we've been told and by that time most of us are too beaten down and apathetic to do anything about it. This thorough and upfront critique could pass for the Cliffs Notes of the American condition. It's a must read for every citizen.