Rules Of Engagement

A hopefully smart look at the frequently not-smart discussion around boundaries and inclusion.

This essay is being cross-posted on Substack, which is no longer hosting my subscriptions. Visit The Reframe to see it on the main site.

So let's say I say something and it hurts your feelings or makes you feel belittled and excluded. Now, let's say you tell me about it. Now let's pretend I say something like "oh my God, I'm so sorry, tell me more." And then let's pretend that you tell me more, and I listen, and apologize, and the next time we interact, when I have a chance to say the thing that hurt your feelings and belittled you and made you feel excluded, I don't. I say something else. And then let's say that later, I check in to see if that interaction was more amenable to you, and if there are any further adjustments I need to make.

You'd probably decide that, based on this exchange, I care about your feelings and your inclusion, and, by extension, I care about you.

Or let's say we're on the subway in rush hour and it's a little crowded on the car, and I step on your toes. Say you tell me about it in this sort of fashion: "Ow!" or "Youch!" or "Gadfreys! My toes!" Now let's pretend that I respond by getting my foot off of your toes, and apologizing, and asking how bad the hurt was. And if the hurt is bad, maybe I even help you get to some medical care. And the next week when we see each other on the subway, you notice that I watch where I step.

You'd probably decide that, based on this interaction, that I care about your bodily autonomy and well-being, and, by extension, you.

Now let's say that I have a couple different reactions. Let's say that when you tell me that what I said made you feel hurt and belittled and excluded, I told you that no actually it didn't hurt you, because I hadn't meant to do that to you, and also other people tell me that they're fine with me saying to them what I said to you, and also that everyone is far too sensitive these days and being told that things I say are harmful is actually very harmful to me, and also the act of you telling me that I've hurt you is a divisive condemnation of me as a person, and being told that I'm a bad person makes me want to hurt your feelings even worse, and if I can hurt your feelings badly enough that you cry it will bring me a lot of joy.

Or let's say that when we are on the subway and you say "Gadfreys, my toes!" I look you dead in the eye and tell you that I'm sure your toes are just fine, and then I stomp on your toes, as hard as I can, and smile, and when you look down you notice that I am wearing boots that seem designed specifically for stomping. And then I kick your shins. And wherever you put your foot, I stomp, and whenever you ask me to stop, I tell you I have no idea what you mean. I tell you that I can't hurt toes because I never intended to hurt toes, and in fact I don't even see toes, and it's people who are always making everything about toes who are responsible for toes getting stomped, and moreover I have no idea what boots even are, or how they could possibly hurt toes, and even more importantly, you are planning to step on my toes, which is why I am justified in stepping on yours.

You'd probably determine that I don't care about your feelings, or your inclusion, or your bodily autonomy or well-being. You might even conclude that I'm actively opposed to those things, and, by extension, actively opposed to you. You might decide I'm not a safe person to be around. You'd almost certainly recognize that I'm not any fun to be around, and that it would be better if I were not in your life. So you might stop interacting with me, not because you think it is bad to interact with people, but because you now know that I am a dangerous asshole. You probably wouldn't smile at me on the subway. You'd probably make a point of being places I'm not.

Now: Let's say a whole bunch of people scolded you because you were shunning me, on the rationale that shunning is bad for a society of inclusion and for the mental well-being of the shunned party, and so that means you are obviously opposed to creating an inclusive society. Let's say a whole bunch of people decided that your decision about how to minimize your interactions with me should be framed not as something you had done because of me, but rather something you were doing to me. Let's say a whole bunch of people decided that you were the author of your own suffering, because your decision to create distance between yourself and the harm I'm doing you isolates me, and isolation can naturally leads to more bad behavior, so it is you who are most at fault for my bad behavior. Let's say a whole bunch of people told you that they had talked to me, and based on what I had told them, the behavior you were reacting to was rooted in ignorance, not malice—and so it was now incumbent upon you to teach me better, and if you refused to do so, then aren't you really the one responsible for your own damaged mental and physical health? And let's say that everyone decided that the lesson to learn from your broken toes is that we need to be a lot more accommodating, as a society, to all the meanest people wearing stomp-boots we can find.

Let's say that a whole lot of people tell you that what is most needed is unity between them and all of my fellow stomp-boots, in a way that makes it clear that this will be a unity that completely fails to consider your existence, in much the same way as I claim I cannot detect the existence of your toes.

Perhaps you see where I'm going with this.

Perhaps I should just tell you.

The Reframe is totally free for all readers, and is made possible by its readers through voluntary subscriptions.

If you find value in these essays, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor. It really helps writers to have patrons.

Before I tell you, let's just say a few things so they are said.

First, there is a lot of propaganda and misinformation out there, and education has been badly damaged over the decades, all of it very much by malicious design, and this absolutely has created a terrible epidemic of badly-informed people. As a result, we have millions of people who are terrifyingly ignorant about matters of observable fact across a terrifyingly wide array of very important subjects.

So there are definitely people out there who voted for Donald Trump and the rest of his fascist party without fully understanding the consequences of voting for a corrupt proto-dictator who intends to create an authoritarian ethno-state in which freedom of speech, assembly, and religion are a thing of the past, in which the rights of marginalized people are stripped away, in which there will be mass deportations and work camps, in which there will be corrupt cronyism on an unimaginable scale, in which we will see the end of government protections of citizens against the excesses and abuses of corporations and hate groups, in which women are deemed property and in which anyone who falls outside of the defined gender roles set by a bunch of totalitarian apocalyptic religious creeps will be punished into submission or killed.

There are definitely millions of ignorant people out there who voted for Donald Trump and the rest of his fascist party who didn't even know those things were on the table, for the very good reason that they never bothered to find out.

There are also millions of complacent people who voted for Donald Trump and the rest of his fascist party who don't believe those things will really happen, for the very good reason that they don't want to believe they will happen.

So some are confused, and others are ignorant, and still others are complacent. They might be reached, because I imagine at least some of them actually don't want all these terrible things that they voted to bring about, and they are going to be very surprised and shocked when those things start to happen, and while people who are fooled would often rather die than admit they've been fooled, still for some this shock might well be an occasion for us to help effect change in their suddenly open minds and hearts. Right now Donald Trump is appointing the most disgusting gang of incompetents and perverts imaginable to high positions of power over the lives and bodies of all the rest of us. A right-wing extremist news personality with Nazi tattoos to head up Defense. A brainwormed vaccine denialist and antisemitic conspiracy monger to head up Health and Human Services. A spineless toady at State. A child rapist as Attorney General. In a field of millions of voters, there are going to be at least a few previously ignorant or confused or complacent souls who see all this, and think to themselves, in the immortal words of Scooby Doo, "ruh-roh."

And it might be good to see them escape complacency and move into conviction, these confused and ignorant and complacent people; it might be good if we are able to see them escape ignorance and move into awareness, or escape confusion and move into clarity.

Now I wanted to make all these points for two very good reasons, first, they are all true things to say, and it is important and powerful in an age of lies to state simple truths simply; and second, these true things are often deployed in service of arguments that represent some of the highest-grade fascism-accommodating bullshit you can possible imagine.

This should come as little surprise. Truths are often deployed in service of lies; this is done by deliberately placing those truths over deeper or more salient truths, and that's the case here as well. Facts are often deployed in service of enabling fascism, by totally ignoring a couple other truths which, in an age of rising fascism, carry overwhelming importance.

Those often-ignored facts are:

Fact 1) Malicious people lie about their intentions, and pretend to be confused and ignorant and complacent to disguise the malice of their intention until it is too late to prevent them. Because of course those who voted for Donald Trump and his fascist party are not exclusively the confused and ignorant and complacent; there are also tens of millions of malicious people among them who very much want all those horrible things to happen, because they are supremacists who believe that some people matter and others do not, and so in the suffering and death and exclusion of millions, they see some advantage of identity or power or wealth to secure. There are even millions of supremacists for whom the thought of others suffering brings them some sort of dark emotion that they think of as "joy," so much so that they are willing to forego advantage and suffer hardship in order to see that greater hardship come to others. And a lot of these folks are still (for now anyway) pretending ignorance, feigning complacency, and lying about their intent.

So some are malicious, and are unsafe people. They simply aren't safe to be around. It's going to be important to recognize them, and create as much distance as possible between them and those they intend to harm—not because we don't see their humanity (no matter how much they may have degraded it through their desire for or indifference to human suffering), but because we respect the humanity of those they will harm far too much to be confused or ignorant or complacent about their clear and hateful intentions.

Fact 2) People who support malice not out of a deliberate desire for malice, but out of confusion and ignorance and complacency are also unsafe people. Somebody swinging a machete around a dancehall doesn't stop being a menace just because they're confused and think that the dancers are zombies, or because they're ignorant and don't know what a machete does to flesh, or because they know but they don't think it's likely they'll hit anyone, and don't care enough to listen to the warnings coming from all around.

Everyone who voted for Donald Trump and his fascist party must be considered to be, on some level, an unsafe person. The act reveals either a desire for violent predation of the strong upon the weak, to be enacted on levels of racial and religious bigotry and sexual dominance and power and wealth, or else an indifference, or else an ignorance, but in any case the person who has managed to get themselves to such a place cannot be assumed safe, and must in fact be presumed unsafe. Some of these people might learn to become better human beings, and we might hope they will, but first we must recognize that everyone who voted for Donald Trump and Republicans is an unsafe person to all the rest of us, and even to themselves.

It's going to be important to recognize this, so that we can create as much distance as possible between them and those they intend to harm—not because we don't see their humanity (no matter how much they may have degraded it through their desire for or indifference to human suffering), but because we respect the humanity of those they will harm too much to think that their confusion or ignorance or complacency on matters of violent hate and malicious intention makes them safe.

And when we make this space, however we make it (because of course there are a lot of situations and the way that we set boundaries and obstacles will have to be situational to suit our ultimate goal of keeping fascists from their intended victims) then those who support fascism will become isolated from the rest of us.

And when that happens, because isolation is not healthy, there will be those who will scold us that our decision to set boundaries and obstacles between people who have proved themselves unsafe and the rest of us is something harmful that we are doing to them.

And those scolds aren't safe people either, those millions of people who agree with us that fascist intent is bad, but refuse to leave the fascist frame, and so insist that everything that fascists do has an understandable motive, by which they mean not that it can be understood but that it must be exonerative; who refuse to leave the fascist frame that insists that anything that is done to resist fascist intention is something that is being done not because of, but to, the fascist.

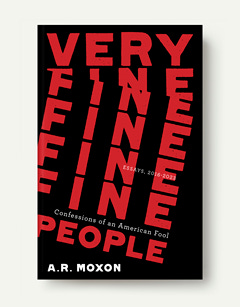

My book of essays, Very Fine People, is now available. Click to buy personalized signed copies or direct purchase at a discount.

Let me make one more point before landing on some conclusions. In this coming age of fascism, it's going to be just as important to discover safe people as it is to discover unsafe people.

We might even find them in unlikely places. You never know who out there might finally be forced to face reality, and turn away from the grotesque course they have set, and become something better than they have been.

How? Well, let's keep it simple.

If somebody is a clear danger, just get away. Keep yourself safe.

But how about three practical rules in places where you might not be sure?

1) When somebody hurts you, tell them. When somebody steps on your toes, let them know that they stepped on your toes. See how they react. They'll tell you who they are.

2) When somebody seems too unsafe to trust with your pain, set a boundary. If somebody has proved themselves less safe than you thought, but you still think it's safe to do so, tell them that you're going to have to withdraw in some way from them. See how they react. They'll tell you who they are.

3) When somebody seems too unsafe to trust with your boundaries, leave. If it's not safe to tell them, or you're not sure if it's safe, withdraw from them without telling them. See how they react. They'll tell you who they are.

Let's unpack these rules a bit more.

When somebody hurts you, tell them.

How does somebody of good will react to this information? They apologize. They ask questions designed to learn how the offense was given, and how to avoid future offense. They change their behavior. They make a real effort to never hurt you in that way again.

You know what a person of bad will does when told they've hurt others? They deny the other person's experience. They tell you the offense didn't happen, and if it did happen it didn't hurt you, and if it did hurt you then the injury represents only weakness on your part. They attack you, or try to throw some unrelated offense in your face, or question whether the pain you felt is real. They immediately cast around for excuses or deflections to establish their innocence, or try to force you to accept that they are innocent before they will even consider your complaint, and then if you give them what they demand they'll still refuse to consider it. They focus on their intentions in an attempt to exonerate themselves of their actions and the effects thereof, and they go looking for other people who will forgive them as proxies on your behalf.

And people of good will who witness this exchange also orient themselves around minimizing the hurt done. They never act as if your report of the offense is itself the offense, or that it is the reason for the offense, or that the offense of your complaint now excuses any future harm from the one who hurt you.

Meanwhile, people of bad will who witness the exchange will become those proxies for the person of bad will, forgiving them on your behalf in the name of redemption before they have done anything redemptive.

When somebody hurts you, tell them. They'll tell you whether or not they are safe, and if they're unsafe, they'll tell you possibly without even knowing. And then you'll know, and so will people of good will who are watching.

And then together we'll stop trusting them with information about us, because we don't trust them, because they have shown that they are not safe people.

This essay is cross-posted on Substack from The Reframe, a free publication supported by its readers through a pay-what-you-want subscription structure. (Click for discount codes.)

Want to make sure you never miss an essay? Subscribe on the main site.

When somebody seems too unsafe to trust with your pain, set a boundary.

You know what a person of good will does when they are asked to respect a boundary? They respect it. They don't try to force their way across it in order to establish that they have the power or the right to do so. They don't treat the boundary as if it is something being done to them, and they express genuine concern for the harm that they have done, which might make such a boundary necessary, and they maybe even work without crossing the boundary you set to become the sort of person from whom boundaries might no longer be necessary, not to gain some reward of forgiveness from you, but because they want to become better people, and no longer want to hurt others the way they hurt you.

You know what somebody of bad will does when a boundary is set? They disregard it, or pretend you didn't set it, or smash it. They take pleasure in the distress that a smashed boundary creates. They frame the boundary entirely around its effects upon themselves and their reputation, and treat the boundary as not only foolishly unnecessary but also an unforgivable aggression against their own personal liberty, justifying any future aggression delivered in return, as well as a post hoc excuse for any aggression that came before.

And people of good will who witness this exchange will orient themselves around respecting the boundary and demanding that those against whom it has been set respect it as well.

Meanwhile, people of bad will who witness the exchange will join the chorus of those who insist that it is the boundary against abuse that creates the division, rather than the abuse itself, and then mourn the division without ever touching upon the abusive causes.

When somebody seems too unsafe to trust with your pain, set a boundary. They'll tell you whether or not you were right, and if they're unsafe they'll tell you possibly without even knowing. And then you'll know, and so will people of good will who are watching.

And then together we'll stop trusting them with our presence, because we don't trust them, because they are not safe people.

When somebody seems too unsafe to trust with your boundaries, leave.

Do you know what somebody of good will does when somebody close to them leaves them without a word? They ask where the person has gone, out of genuine concern for their well being. They seek them out, not to disparage them, but to offer what assistance they can. And if they find the person has withdrawn because of their own behavior, then they act in the same way that a person of good will acts when they learn they have committed an offense, the same way a person of good will acts when a boundary is established for them to respect.

You know what somebody of bad will does when somebody leaves? Some may not ever ask where the departed person has gone, because they wanted them gone, and they're indifferent to where or why or how. Otherwise they rage, not because they care for the departed person, but because they care about what the absence might suggest about themselves, or because they consider the other person their possession. They will seek the person out, not to help them, but to recapture and punish them. They'll try to gather allies together to seek them out, demolish the safe spaces and the zones of joy that can only exist in their absence, and then when they've completed their demolition they'll credit themselves as justified based on the unforgivable crime of having absented yourself from their presence before they were properly done with you. They'll treat you as if you have stolen your very self from them, because the final truth of bullies is that they are the expendable ones, from whom we all can walk away without any harm; they need us in ways that we will never need them; a bully needs victims, but victims have no need of bullies.

And people of good will who witness this unfolding will orient themselves around protecting a person who hides from their tormenter, and refuse to acknowledge the location of the tormented.

Meanwhile, people of bad will who witness this unfolding will join the abuser in the hunt for the abused.

When somebody seems too unsafe to trust with your boundaries, leave. They'll tell you whether or not you were right, and if they're unsafe they'll tell you possibly without even knowing. And then you'll know, and so will people of good will who are watching.

And then together we'll stop trusting them with anything at all, because we don't trust them, because they are not safe people.

So there you go. Rules of boundaries and rules of engagement (or disengagement, or non-engagement). Uncomfortable to practice, perhaps, in this coming age of fascist retribution that Republicans and white christians and neo-Nazis and other types of confederated hate groups promise us is coming as they laugh and sneer and gleefully anticipate their dark advent of pain; but practical all the same, and simple enough to codify.

We're all in this together, all of us who want to celebrate our shared humanity. Those of us who want to not be in it together, who would rather claim all space for themselves and their own domination, are going to get a lot of what they want, because they are about to get the power to do it. I don't think it will make them happy, because I think they are shunning their own humanity, but they belong to themselves so we'll have to leave them their own spiritual fate as their humanity diminishes and dwindles, so we can focus on protecting the rest of us as best we can from the storm they'll bring.

And so we find each other, and make what safety we can, and we will find happiness there, and even joy.

Anyone can join us in shared humanity and solidarity if they want to, or at least I hope we are the kinds of people who feel that way, and can recognize when somebody who was worse becomes better. But in order to want to join us, they have to ... well, they have to want to. If they want to, then they'll do the things people who want to join shared humanity do, which will mean we'll find them wearing softer shoes and treading a lighter step.

Anyone who doesn't want to, won't. And they'll tell us without even knowing it.

And I dearly hope we will be people who recognize the difference.

The Reframe is totally free, and is supported voluntarily by readers.

If you liked what you read, and only if you can afford to, please consider becoming a paid sponsor at The Reframe. Pay whatever you want.

Click the buttons for details.

Looking for a tip jar but don't want to subscribe?

Venmo is here and Paypal is here.

A.R. Moxon is the author of The Revisionaries, which is available in most of the usual places, and some of the unusual places, and the essay collection Very Fine People. You can get his books right here for example. He is also co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media which goes in your ears. Breath and burning, he is made of sand.