Sabotage: Part 7 - Compromise & Hope

The second sabotage is sabotage of our conviction with complacency—a sabotage enabled by a purposeless compromise that exists for its own sake. The big question is: How do we counter it?

Note: this essay was originally published on Revue on September 25, 2022.

Intro | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 |

Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 |

Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 |

Let’s recap, very briefly.

Most of us want to see what is broken get fixed, and yet repair seems far from us, because the process of repair has been sabotaged.

Our awareness of brokenness has been sabotaged by deliberate ignorance enabled by a morally empty neutrality.

Our conviction to fix brokenness has been sabotaged by a multi-faceted complacency.

OK. Good? Click those links at the top for more detail if you want it.

°

As I see it, every sabotage rests upon blameless supremacy, which refuses to pay any of the natural costs of maintenance, improvement, and repair, or to accept any blame for refusing to repair, and chooses instead to profit from making everybody else pay the much higher unnatural costs of brokenness.

As I perceive it, each sabotage is accommodated by its own enablement.

The enablement of the second sabotage—which, again, is the sabotage of our conviction with complacency—is something I’d name compromise.

Wait.

Pause.

Compromise is a bad thing? Really? Compromise enables supremacy?

Isn’t compromise something mature adults do to solve problems in the real world? Isn’t compromise the thing that realistic sober-minded people do to enact the sort of strategic incremental advantages that lead to real change?

I hear you. I really do.

Now let me tell you a story.

In 2018, a U.S. president whose name escapes me at the moment disbanded the U.S. pandemic response team, which had been established by his predecessor. Old What’s-his-name was shutting down a lot of things set up by his predecessor around that time. This might have seemed petty and political and biased to a news media that typically hates bias and petty politics, but this move was about saving costs, after all, and we don’t like paying costs, and anyway we weren’t in a pandemic at that moment.

In 2019, a virus showed up called Covid-19, and that president did nothing about it, which is a polite way to say that he actively and categorically opposed doing anything about it, even going so far as to lie about what he already knew the effects were going to be, and to oppose the testing that any epidemiological response would include, and he pushed quack remedies, and … look, it feels like a fever dream, but … I’m pretty sure he suggested we apply sunlight to the lungs and inject disinfectant. This would have been very funny, if it hadn’t been such serious business—which it was, because this virus is virulent and airborne and deadly and disabling, all qualities that land solidly in my top 10 least favorite attributes for viruses.

Anyway, our public health apparatus moved to do the sorts of things that are necessary in times of an airborne virulent deadly disabling virus, and most of us—because we did not want to become dead or disabled—moved to comply. This included directives to wear masks in public, and to shelter in place, and to close down all non-crucial businesses, and (because our society is organized in such a way that you must earn life by working) to pay people to do that, and so forth. All the while, Old What’s-his-name did everything he could to oppose and undermine those efforts: refusing to wear a mask, or to shelter in place, and continually insisting—even as the bodies piled up and our infrastructure (which, to avoid costs of maintenance, had not been maintained to prepare for a pandemic) creaked dangerously, and our health care workers quickly were strained to the breaking point—that we return to normal, which to him mostly meant that we stop acting as if we were in the global pandemic we were in.

Old What’s-His-Name, who was not all that big into subtext, was quite shockingly clear that he opposed fighting the virus specifically because to fight the virus meant acknowledging the virus, and acknowledging the virus carried a responsibility to do something about it, and doing something about it would get into money. Even worse, that money would have to be given by people who had all the money to people who didn’t have any of it, and, given our dominant cultural belief that people who have money deserve money and people who don’t have money don’t deserve it, paying people to live who weren’t doing the work necessary to earn life started seeming extremely morally hazardous, especially to people who were wealthy—people like (perhaps coincidentally) Old What’s-his-name himself.

And all the people who looked to Old What’s-his-name for identity and meaning and purpose took on his viewpoint—which was that the attempt to keep people alive wasn’t worth the cost, and that in fact the cost of keeping people alive was theft, and was in fact the worst possible form of tyranny, and there was a general opposition to masking on ostensibly moral but observably selfish grounds, and in my state some of them came and took over our state capitol and tried to kidnap and murder our governor, a woman who Old What’s-his-name was vilifying on a daily basis while refusing to send my state much-needed ventilators for the crime of having elected such a woman.

The upshot was, we got people back to work as quickly as possible, and shut down the relief money as quickly as possible, and we created a relief loan system that made a top priority ensuring that nobody undeserving got any money, which meant that it was administratively difficult to get the money, which meant that it was far easier for people who had money to get the relief money than it was for people without money to get it, and we had a massive tax giveaway to the wealthy, and some massive corporate bailouts, and then we saw the greatest increase in wealth disparity of all time.

And I suppose that, for those who happen to share the dominant cultural view that people with money deserve money and people without money don’t deserve money, this was all very comforting.

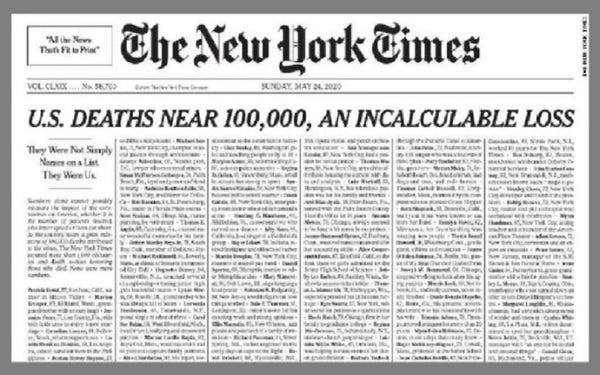

During that time we crossed the threshold of 100,000 people dead, which was pretty easy for us to do, given that people were dying by the thousands every day.

The New York Times called it “an incalculable loss,” which it was, for many reasons, not least that we refused to calculate it.

And then another million people died, and so forth.

And we’ve seen a near-daily barrage of opinion pieces insisting that the pandemic is over, from the day it began until now, most of which make the point that people who insist on acting as if we are in the global pandemic we are in are very distracting and annoying to everyone else.

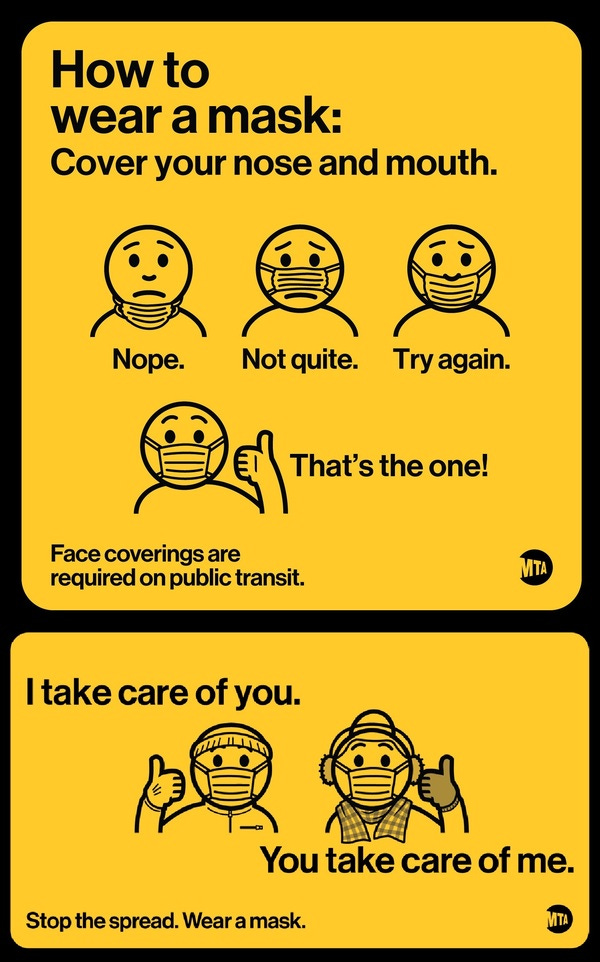

And last week, the New York transit authority put out some new posters promoting a “you do you” masking policy, which frames mask wearing as an entirely personal choice—the exact framing that the followers of Old What’s-his-name demanded two years ago. One gets the sense (if one is me) that the purpose of the campaign is to curtail harassment—not of people who don’t wear masks, but of those who do—of those who still choose to commit the offense of reminding people that the virus still exists, and therefore returns them to the ever-present conviction to do something about it.

I’m not sure if we ever got around to learning how much money we saved by shutting down the pandemic response team in 2018, by the way.

It must have been an incalculable amount.

Republicans are running for office this year, as they do, and they promise to shut down most other government functions as well, for the unspeakable crime of taking tax money from citizens and using it to take care of citizens.

It looks like they might just win.

Think how much money we’ll save!

But we were talking about conviction, and sabotage of conviction.

°

If you recall, I was saying that the accommodation that enabled sabotage of our conviction was compromise. I then pretended that you were shocked by this for rhetorical effect.

Compromise is bad? you’d asked me. Isn’t compromise necessary?

OK, settle down. I’ll answer you. Damn.

I think it’s important to understand that every accommodation of supremacy involves invocation of something that is positive in times of health—the fruits of a healthy society. Blameless supremacists know that there’s a natural human instinct to want health, and the good things that come with health, and so they point to the trappings of health and demand we enact them, to prove to them that we really are people who want healthy things.

And we accommodate them.

Neutrality, for example, which when applied to a deliberate ignorance enables sabotage of our awareness, isn’t inherently bad. Neutrality when applied in healthy times allows many valuable things: open-mindedness, exchange of ideas, unbiased journalism between competing ideas of merit. It’s bad when it’s improperly applied to deliberate ignorance, specifically because it sabotages our awareness.

So too with compromise.

I’d ask you to think of compromise as a tool. It’s helpful to do so, because we don’t tend to think of tools along lines of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ but rather along lines of use. A lawnmower is an excellent tool for creating an even-length lawn, but a very bad tool for a kidney transplant. It’s a great tool in the hands of a landscaper. It’s a terrible tool in the hands of a surgeon.

When you have multiple parties that all agree that there is a problem to solve, but don’t agree on the methodology to solve it, compromise is an excellent tool for negotiating those differences—and even when two parties don’t agree that there is a problem to solve, it can certainly be the responsible and realistic choice to give up some of your preferences in order to achieve most of your main goal and establish a better position whereby to achieve the rest. If those making the compromise understand how the compromise is getting us all closer to an end goal of repair, and the strategic worth of what they are gaining, and what their opponent is giving up in exchange, and how they intend to use their better position, then yes, compromise can be appropriate and necessary.

All too frequently, though, we see a compromise that exists only for the sake of itself.

What would we think of a landscaper who used only a lawnmower? Imagine a landscaper who used a lawnmower to trim the hedges, or weed a flowerbed. Imagine a landscaper whose goal was not to make the landscaping look nice, but simply to use their lawn mower. Who never looked to the results of their work, or considered other tools that might be more apt. Would we say that person is being a clear-minded grown-up, or a dangerous fool?

Compromise can be an excellent tool. It’s a terrible goal.

If we set our compasses toward compromise as our final destination, we’ll never go anywhere.

Blameless people know this, by the way.

°

It’s 2022 now.

Let’s see what’s up in 2022.

Well, we’ve replaced Old What’s-his-name with Old What’s-his-face, for starters. That’s promising. The new guy’s name is Joe, and I think that’s he’s better than what came before, in the same way that a casserole makes a better meal than a plate of cold cat shit. I guess what I’m saying is, you don’t even have to ask what kind of casserole.

But Joe just took an interview where he said the pandemic was over, even though a hundred people died today, and a hundred died yesterday, and a hundred more will die tomorrow, even though the stories about long Covid are many and devastating.

They’re walking it back a bit now.

But earlier, Joe’s administration announced that Covid was a “pandemic of the unvaccinated,” by way of encouraging people to get vaccines, to be sure, but also by way of supporting the by-now quite popular belief that those who don’t get the vaccine deserve what they get, because of the choices they’ve made. And, sure enough, there are people who have chosen deliberate ignorance, and decided they’d rather die than get a vaccine, and Covid has sure enough taken many of them up on that proposition; but there are millions of people who cannot get the vaccine, and we all know it.

And we aren’t funding tests anymore; Republicans are still as opposed to the tyranny of tests as they are opposed to the tyranny of vaccines, and there are enough Democrats that agree that I guess there won’t be any more funds for it, and I guess there’s nothing to be done about that.

And nobody wears masks pretty much anywhere, but we’re asked to respect the choices either way. It’s a personal decision now, whether or not to spread a deadly and debilitating virus. Just look to the subway signs.

If you look around, you’ll see it. We have won the victory over ourselves, successfully overcoming the natural human instinct to give a shit.

Two years ago, most people were of the view that we ought to do what it took to oppose a global pandemic; and that we all were interrelated in ways we couldn’t extricate ourselves from even if we wanted to, and that it was the responsibility of the healthy to see to the well-being of the sick.

But a loud minority insisted that the only thing that mattered was acting as if there were no pandemic, and that the only viewpoint that mattered was theirs, and the only risk they were taking in flouting health guidelines was to themselves, and that any deaths that came were inevitable, and that to mourn the deaths was an unseemly display of politicization, and to expect anyone to participate in caring for the sick was not only unrealistic but immoral theft and authoritarian tyranny, deserving whatever violence they decided to enact in retaliation.

Eventually, most of us of the former view have come around mostly to their point of view.

We gave in on everything, and they gave in on nothing.

It was a compromise.

Where was I?

Ah yes. As I said, somewhere in there we crossed a million deaths, which I’m told was inevitable, because all viruses are endemic, and we didn’t have any significant period of mourning to mark the occasion of 10 times an incalculable amount.

I guess we got better at calculating loss.

Again: blameless people know that most of us have a natural human instinct to want health: for ourselves, for our family and friends and neighbors, even for strangers. They know that even in unhealthy times, there’s an instinct to pursue the trappings of health like neutrality and compromise, and they will capitalize on this instinct to achieve their ends. They won’t offer us health, because health will involve repair, and repair involves costs that include their own advantages and their own blamelessness—but they’ll use our desire for health to achieve their own ends. They’ll offer compromise, and many of us will take it, giving up our conviction without thought to an endpoint; giving up and never noticing that blameless supremacy gives up nothing and never will, without remembering that they have reneged on every promise.

There’s a thing I wrote on Twitter years ago that still gets passed around.

It goes like this:

A.R. (Actually Republic) Moxon @JuliusGoat

Meet me in the middle, says the unjust man.

You take a step toward him. He takes a step back.

Meet me in the middle, says the unjust man.

2:05 PM - 23 Mar 2019

I believe this little scrap of free verse took hold because it describes something we have all seen: a sabotaged conviction accommodated, for no purpose other than moving us in the wrong direction.

What the blameless society asks us to do is more than compromising on our method for achieving a solution, or to horse trade one goal for another toward a solution that we both agree upon. The demand is that we compromise on our conviction to seek any solutions at all.

Why are so many of us afraid to seek solutions?

Have you even noticed that we are?

We are, you know. We’re afraid to try.

I say this because of how often we don’t even try, and use our fears of failure as justification. Somewhere along the line we agreed that true solutions ought not be pursued, because they are doomed to failure, or impractical, or unnecessary, or are impossible, or even dangerous.

Somewhere along the line we agreed not to try for good and necessary things, not because we don’t want them, but because we imagine somebody else doesn’t want them, and, fearing defeat, we concede without trying.

Somewhere along the line we agreed to allow questions of basic need to be mediated by questions of who deserves them. We decided to stop saying things like “nobody should go hungry” and start saying things like “nobody who works 40 hours a week in the richest country on earth should go hungry without access to tax refund credits for education offsets.”

It’s sabotage, and enablement of sabotage.

You’ll know our conviction has been sabotaged, because you’ll find that even very fine people who seem to agree with progressive motion toward repair begin to accept the blameless society’s framing. You’ll hear the natural final destinations of repair—justice, maintenance, improvement, equality—framed as being intrinsically undesirable.

People who want immigration reform will start by assuring everybody that “nobody wants open borders,” even though open borders should always be our desired goal—because a country with open borders has achieved such a state of peace between neighboring countries, such a fulfillment of basic human need, such a reduction of strife, that controlled borders between them have become unnecessary.

People who want to reduce police brutality or mass incarceration say things like “nobody wants to abolish the police” or “nobody wants to abolish prisons,” even though a land without police and prison should always be our desired goals, because a land without these establishments is one where peace has taken such natural sway, one whose laws are so just and whose institutions so well attuned to their spirit, that enforcement has become unnecessary.

People who want economic justice say things like “nobody wants education to be totally free” or “nobody is saying we should just give people houses,” even though it is far less expensive—from not only a moral standpoint but a practical economic one—to care for everyone than to pay the cost of not caring for everyone; even though the only reason not to do so is because we have believed expensive lies that insist that life must be earned, and to receive life without doing so is theft; even though disentangling the urge for productive work from the need to struggle for survival has been an intrinsic purpose of natural human systems from the beginning. These are expensive lies founded in a false framework of scarcity, which insists it is better to spend five dollars on solution management to prevent one dollar from reaching undeserving hands than to simply allow the natural abundance our natural human systems generate to distribute that abundance, in ways that benefit us all.

You’ll hear “good luck doing that in this political atmosphere,” as if atmospheres can’t be changed, as if the sight of somebody trying a difficult necessary thing can’t inspire others to believe in new possibilities. You’ll hear people afraid to even ask for better things scolding others who demand them, for fear of alienating people who are opposed to better things, for fear of losing the support of people who will never lend their support to any effort worth supporting.

You’ll hear many things like this, in a blameless society—a self-inflicted sabotage of our compass’ final destination, self-inflicted sabotage of an end goal we should all seek, even if a perfected state is unlikely. You’ll hear people talk about unlikelihood as a way of preventing the journey from even beginning. It’s a subtle despair, a belief not only that the endpoint of a perfected natural human system is not only unattainable, but so unattainable as to make even the desire for it a dangerous and fearful thing.

We’ve been talking about our pandemic response, but we could be talking about thousands of other messages that come to us every day. The sabotage of our conviction is in the atmosphere.

Supremacists sabotage our conviction with complacency—cold indifference, blinkered institutionalism, pre-defeated cynicism, empty optimism. But the accommodation is the supremacy, and compromise makes ignorance successful.

Once we’ve agreed to occupy the frame of the blameless society, we remain inside their picture. We never take the journey our compasses have set, because we have agreed that not moving is a preferable option, even if we know not moving is unsustainable and ensures disaster. We’ve agreed in endless tiny conscious and subconscious ways with the saboteur’s framework: that the uncertainty of the journey guarantees certain failure, that our present unsustainable status quo is safest because it is most familiar, that change is impossible and therefore undesirable, and that we can never take any journey without first securing the permission of those who refuse to go. And all of it rests upon a sabotage of our conviction: a refusal to believe better things are possible, or that we can bring it about.

So now I want to answer the big question, which is what do we do about it?

I want to talk about hope.

°

I’m not talking about a hope that crosses its fingers and closes its eyes and wishes for the best, or a hope that just keeps its eyes on the ground and refuses to look at a problem that it insists will solve itself. That’s optimism, hope’s counterfeit, which is just the friendliest flavor of complacency.

I’m talking about a hope full of rugged resolve; a hope that looks clearly at a situation that is dire and refuses to look away. I’m talking about a hope that allows you to look at unlikely but necessary change in full awareness of how unlikely that change is, and try for it anyway—not because the change is likely but because it is necessary; because somebody has to try, and you are somebody. This is the sort of hope that makes you fight even when victory is far from assured. This is the sort of hope that refuses to hand its opponent easy wins simply because support seems scant and a loss seems likely. This is the sort of hope that rallies in the final minutes and brings the crowd to its feet. It’s the sort of hope that is willing to pay a high cost for victory when defeat isn’t an option. It’s a hope that is willing to be beaten and then try again.

It’s the sort of hope that changes the atmosphere, which changes what is possible.

It’s a hope that makes unlikely change possible, then likely, then inevitable.

I hope you’ll agree, we need a lot of unlikely change.

If you agree, I have good news: unlikely change happens all the time.

In fact, most major changes throughout our history—emancipation, women’s suffrage, The New Deal, the labor movement, the civil rights movement, gay marriage, the 40 hour work week, the weekend, democracy—were unlikely at some point beforehand. Before, that is, they all actually happened. They failed and failed and failed and failed and failed … until they succeeded.

What makes unlikely change possible? The same things that always do, I’d say.

I think hope, like reparation, is a sequential process.

Here are the steps I observe:

1. Expect it. If you don’t expect it, start expecting it.

2. Express your expectation by demanding it.

3. Give your demands weight by issuing consequences for those demands.

4. If your demands are ignored, deliver those consequences.

5. Realize permission isn’t required. Work with power and institution if it aligns toward unlikely change, but demonstrate your own power by working toward change independent of power and institution.

6. Repeat. The hope I’m talking about is a cyclical hope.

It’s a hope whose journey isn’t derailed by the knowledge that the journey is hard, because it has a clear vision of the terrain and knows the difficulty full well.

It’s a hope that understands that the world is changeable, and we can change it.

It’s a hope that knows that few victories arrive without defeat as a preamble.

It’s a hope that never seeks easy incremental losses and calls them gain.

It’s a hope that works for what it expects and demands.

It’s a hope that refuses a purposeless compromise.

It’s a hope that rejects cynicism’s predetermined defeat without losing cynicism’s ability to recognize the problem.

It’s a hope that knows that there are people of bad intention, who hoped for a less equal, authoritarian, corrupt, bigoted country, who hoped to restore white supremacy and bigotry and hatred to full strength, and, because they hoped for it, they’ve achieved it.

It’s a hope that knows we can make a better kinder world, where even people of bad intention will be cared for. It’s a hope that knows we should make a sustainable world that such people will hate and fear, even as it sustains us all—even them.

It’s a generative hope, that knows the sight of people enacting hope will inspire other people to hope as well, which will swell the ranks of those who expect and demand and issue consequence and demonstrate their own power by working for unlikely change independent of power.

Hope dissolves the urge for a directionless compromise that has no goal other than itself.

Hope increases the cost of complacency—and moves to your cause many complacent people whose only goal is to avoid cost.

To hope with resolve for unlikely change is to fight the blameless society’s sabotage of conviction. You’ll know this, because as you move into hope, those convicted by the sight of people acting in determined hope will begin to attack that hope as unrealistic and foolish and dangerous and wrong. They will make sure the price for your hope is as high as they can make it—so you’ll know you’re there, once you start to pay.

I think hope is a powerful tool in our fight against sabotage, available to everyone.

It changes the frame. It changes the atmosphere.

It tells a new story.

And that’s what I think repair looks like.

°

A parting question: why do we need conviction, anyway?

The same reason we need to be aware our streets are broken and be convicted that they should be fixed—because it leads to the sort of open proclamation—a public airing of our awareness of brokenness and our conviction that we should fix it—that puts the process of repair into common currency.

We need conviction, because conviction leads to confession.

That’s next.

_______

A.R. Moxon is the author of the novel The Revisionaries, available in most of the usual places and some of the unusual places, and co-writer of Sugar Maple, a musical fiction podcast from Osiris Media. He likes you, he really, really likes you.